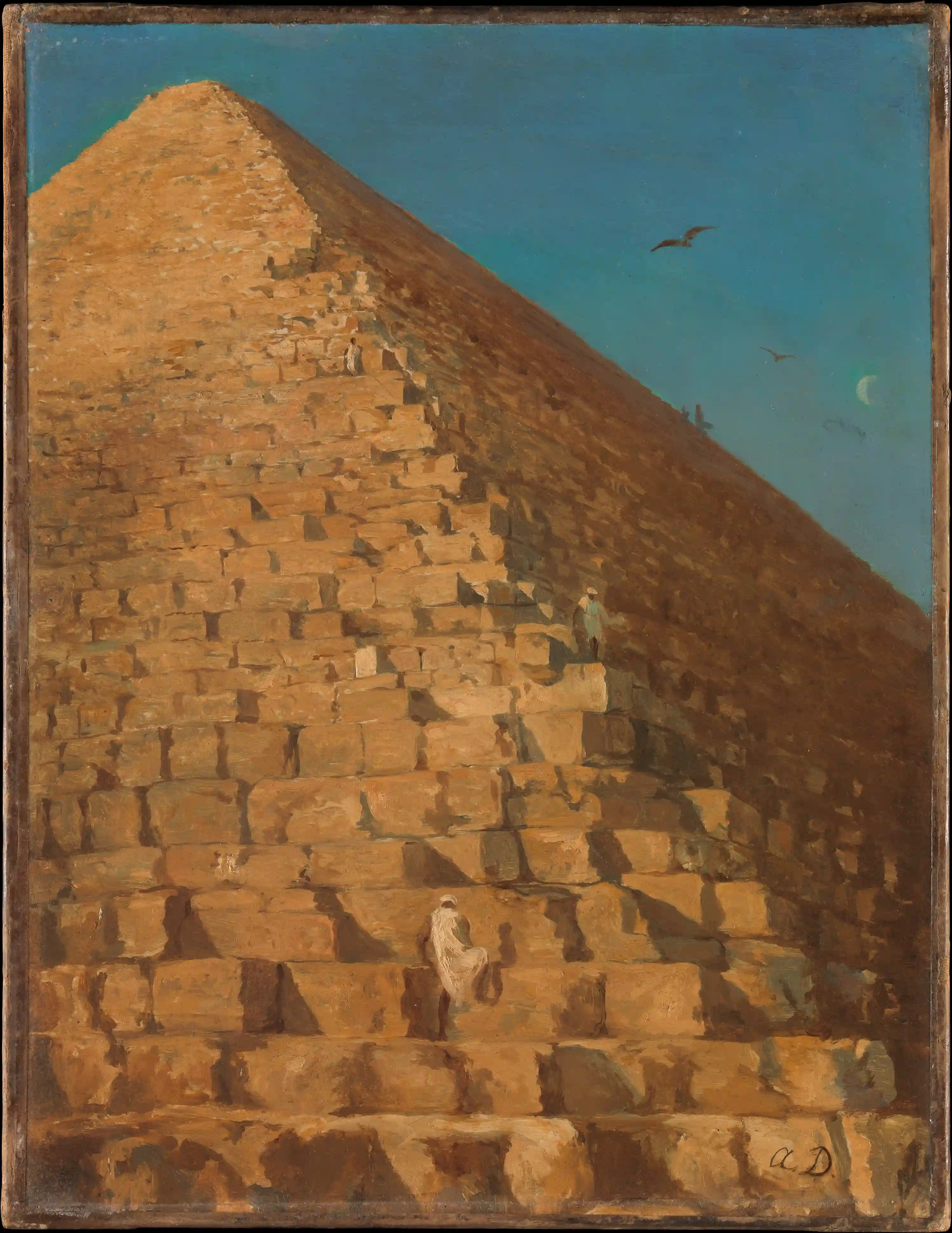

Underworld Scene with a Man and Woman Enthroned and Death Standing Guard, by Robert Caney

Netherworld

“Aren’t you taking Maple?”

“It’s night. Beech will be just as fast. And I don’t have to wait at that light.” They were driving straight down a dark road, their little green car bumping on the potholes. It wasn’t a long drive back to their apartment. Fifteen minutes or so.

“It’s so dark.”

“It’s night. And it’s residential.”

“Still.”

“Yeah.”

They kept driving. The road was long and straight.

“We are completely out of eggs. I just remembered.”

“We could go out for brunch tomorrow.”

“I seriously don’t remember any hill in this city being this steep. Where are you taking us?” Toby asked, her feet on the dashboard compartment in front of her.

Susannah frowned. “Home? I hope,” she joked. “It’s the hill down to Elm, I guess. I didn’t think we got that far yet.”

“It’s not usually this steep, either,” Toby said, yawning.

“I guess after mezcal it is.”

The road kept sloping downward. They kept driving.

“How much longer?”

Susannah didn’t answer, watching the road.

“Susannah?”

“It is too long,” she said, just as the road started leveling out. “We’re not at Spruce yet, though. What the fuck. Did I get us lost?”

“You said you were okay to drive.”

“I was. I am. Just tired.” Suddenly she pulled over to the side of the road too sharply.

“What the hell?” Toby said, jumping back up to a sitting position.

“I just got a weird feeling.” She put the car in park and turned on the brights. They both looked out the windshield.

“Jesus fucking christ. Where the fuck are we?” Toby said.

It was dark, but not like small-city-at-night dark, streetlights-out dark; it was dark like other-worlds dark, things-lurking, monsters-with-many-heads-and-too-long-limbs dark. The headlights only picked out a small circle in front of them. There were none of the trees they were used to, no sugar maples or beeches—instead long black rods, shiny and hard. There were no leaves. Toby flicked her lighter. It blew out.

Susannah was frozen in the driver’s seat, looking straight out the windshield; her eyes flicked over to Toby and then she looked back out again, not wanting to make eye contact, know what they were both seeing.

Something moved outside. There was a step toward the car.

“I’m getting out,” Toby said, moving her hand onto the door handle and pausing to look at Susannah.

“Should we run?” Susannah said, lost, thinking of them racing through that dark hand in hand.

“No. To see what it is. Where the hell are we,” she said again, opening the door. She wasn’t afraid yet. Susannah reached out to grab her by the back of the shirt but just missed.

“Hello?” Toby said out into the wild. Small, soft sounds, like clinking glass tubes. Nothing answered her. Toby looked around more closely, her eyes seeing things. Her eyes dilating and refocusing, strange things being seen by them, going through them and into her, to where she kept herself.

Susannah slid across the passenger seat and went out the same door Toby had. “We can go back. We can drive back the way we came. We just made a wrong turn somewhere.”

“We have to go through,” Toby said.

“What are you talking about?”

“You always have to go through.” For a moment Toby noticed that her voice sounded different. Then she felt it settle into her throat, drop by drop.

“We’re probably dead,” Susannah said, not yet listening. “That’s what happened. I crashed the car and we died.”

A voice spoke near them, very smooth and dark, like honey, or tomato paste.

“You won’t leave. You’ll live in a cabin down that way and light fires every night. You’ll adjust to the dark and grown horns, or feathers.”

“I don’t even know how to build a fire,” Susannah answered automatically, and then heard the voice again and started frantically pulling on the car door, but it had locked. She grabbed Toby’s hand so they’d be together for whatever came next, like once they were touching they were one thing.

Toby took a step forward, farther in.

“Toby.”

She took another, beginning to pull Susannah after her.

“Come on. We’ll go back. I’ll unlock the car. We’ll turn around and drive home,” she said as she walked after Toby. “We’ll come back in the day and see the forest.” There had never been a forest there, though. “We’ll—” She stopped to scream as something touched her on the shoulder. The beast.

“It’s that way. You’re going the wrong way,” they said. Their hand was cold and smooth.

“Answer him, Toby.” Nothing. “Toby.” They were still holding hands, but Toby was walking forward, and the ground was cold and smooth, and the air, Susannah noticed, it was smooth, too, with no wind or movement.

“Shh,” Toby said, but stroking Susannah’s thumb with her thumb, like she did, as if to show it was still her and not a new demon. But the feeling was wrong, as if Toby usually stroked her thumb just-that-fast and now it was a little faster; like her fingerprint had changed, and the top of Susannah’s thumb felt different whorls.

“The garden will grow, and the fire will be dark. The moons will be cold and tall. The garden will grow. You will eat.”

The layers of the ground were changing, some thin and crinkly, some snapping when walked over. Shimmering glass tubes floating in the air, and the ground made a sound like salt flats but cleaner and quieter and with shorter crags.

“Where are you taking us?” Susannah said, trying to hold back the hand that was all she could see of Toby. Toby’s short black or purple-dyed hair, she couldn’t remember which; her flat shoes and thin jeans. She knew those things were there, suspected they even still contained that known body, well known.

“We have to go through,” Toby said. “There’s something we have to see.”

“We could have just gone back out. This wouldn’t even have been real.” But the smell was different, more pure, as if through a mask: nothing can get in, no germs or nice things. It smelled cold, like an ice rink but without the enjoyment, and metallic, but without the sense of blood and all the promises and heat that go with it. And liquid, but not clean or sanitizing or thick, not rainy or musty, carrying no dirt or bugs with it, able to carry nothing. It created a feeling on your skin like all your companions had left you, all the bacteria and leftover days, and you were not cleaner, not more you, but just less thick.

Now things were brushing their shoulders and hair. No wind, no grass; whatever it is is sharp and stiff.

“Where are you taking us?” she asked again. “The thing said to go that way.”

“I have to see,” Toby said. So many things out there. She would not rest at herself.

“But we should go home,” Susannah said. Why would you go to the home a beast said was your home? Wouldn’t you go the opposite? She wanted to hear someone say to her, don’t you know the home a demon makes for you is the wrong one to go to. Where you will be comfortable and grow and flourish on its diet of dark things. But then, if there is a home for you here, it is probably too late to avoid it. You should go in, go under the covers, and sleep.

“No,” Toby said. “We have to look for it.” The it she was talking about was not anything’s pronoun. It had never even been mentioned in a sentence before.

“There’s nothing here,” Susannah said. “It’s just black and cold. There’s nothing here, Toby.”

“No, there is. We’ll find it.” Her hand was getting colder and sharper now, like a glove frozen onto your hand. Warm, in a way. Keeping out the even colder things past it.

“Look at me,” Susannah said. “Or I’m going back to the car without you. I’ll drive out of here. I’ll go home. I’ll eat brunch by myself.” Susannah yanked on the cold hand so hard that Toby was spun toward her. Her eyes were very dark blue, and the blue shone out like her body was full of it. She watched as the brown she thought she remembered saw her and moved toward her and then moved away.

“You can’t get back. The gate closed,” Toby said, or was it the beast.

Toby pulled her hand from Susannah’s suddenly and started running forward, toward one of the cold black thickets, every centimeter full of another long thin black spike. You couldn’t tell if it was sharp or bendy or would break as you touched them, but then somehow Toby was running among them without them moving and without them touching her or breaking, like she was so exact and so used to that place that she could make no mistakes. Or she was the same substance as them and they were all touching, grabbing, combining, recombining, and uncombining so that what looked like Toby now was a thing that was part Toby, part black spiky trees, then part different spiky trees, and the things that had been Toby were now the forest… It looked like Toby. Then she could not see Toby anymore, like Toby had vanished into the third world in this world, maybe even a darker one.

She did not want to go in, she wanted to leave that creature behind and go back to the car and get out of there. But she did because the body was still Toby’s, even if Toby herself had not made it more than a few steps past the car. She should still get that Toby. She crept forward, exchanging herself with the plants, maybe, or walking smoothly and with great versatility, maybe, until she saw a low, black, shiny circle, like a pond, if they had water here, or the inside of a mirror; she declared it a lake and put her hands in.

The water parted, breathable, and she looked down and saw Toby down there. She did not look dead, but comfortable; asleep or resting. Maybe it was warm down there. She yelled “Toby!” into the lake. She thought the sound would hit Toby, maybe wake her up, maybe split her from the black glass molecules she had imbibed. “Toby,” she said again, but nothing answered. “Why would you go in there,” she said. She let herself slither in, face first.

She thought, as she fell, about when she had met Toby. Now she was falling through an abyss for her. Maybe Toby had started out that way too. The woman at the bottom of the abyss, and Susannah thought it was better to join her than to stay by herself at the top. She found Toby, who was curled up on a floor and welcomed her. They lay against each other, knees against backs of knees. It felt familiar to them both but not in the same way.

She had Susannah and also the beast and together they sandwiched her. It was large and terrible and apocalyptic, but you did not care at all. The beast was somewhere up above, and also in her spleen and gallbladder and appendix, the small organs that could get hurt without breaking you. Without breaking you much. Susannah was so good; she wanted to touch her hair, the back of her neck. She didn’t know if she could or should anymore. Susannah’s spleen and gallbladder and appendix, clean and smooth and undamaged, beat against her back with her blood. Susannah sighed in her sleep, working right.

They might have slept there all night, but there was no sun or moon, so they could not tell when it had been the full length of a night. Toby woke first. She could see well in that lake. They were surrounded by something that was like soil but less alive, teeming but not with life, with things. She stuck her hand in, grabbed a handful of whatever it was that came out, examined it. Not like ants, not like worms, but small things that moved and clicked gently. She liked the sounds they made more than she wanted to. More than she would have wanted to. Now she just listened.

Susannah woke up, hearing her move.

“Toby? What is that stuff? Your hands are covered in…” She was going to say dirt, but it wasn’t dirt. “Why did you touch that? There’s nowhere to wash off here.” They were in the water, and the water here did not wash.

“We’re clean,” Toby said, her voice a gentle click, not alive, but more alive than a dead thing.

“Why did you go down here?”

“I had to find the bottom,” Toby said, answering from a part of her that was not already all gone. She sunk her arms and legs into the bottom, trying to find a way out, a tunnel, but the world was at the end here, it was the bottom. “This is the last thing of everything there is,” she explained. “This is the end of the world.”

“So?” Susannah said.

“Now we know the worst that can happen,” and she grabbed Susannah’s head as if to twist it.

Two hands on the back of her neck. Two cold hard hands that gripped her familiarly, familially, like they knew both her head and heads in general, how to twist, but also where the weaknesses in hers were. Where the thoughts were that could be pressed just right to explode within themselves so that the eyes would go blank, looking inside. A touch full of love, somehow. It felt like it could transition into stroking her hair, but it didn’t, it tightened, each hand finding its grip and the proper, most effective place from which to twist, a wrench exploring until the nut fits softly inside. Toby found the spot and closed her eyes, like she was preparing to love every second.

And then she let go and began climbing up out of the abyss, her shoes finding stairs that weren’t there in the smooth glass dirt sides. She walked up as if a spider, and Susannah looked for a softer edge she could make dents in to pull herself up with. She did not move her head or her neck. She was not sure if it was still on. She did not think anything about that. Toby’s hands had not been warm, but they had some of the same feel they used to, some of the same bends and lumps and patterns. She climbed up the wall and met Toby at the top.

Susannah began to lead them to the hut. It was her turn now; Toby must have done whatever she came here to do. Susannah wanted to know what was in their home now, more than before. Was it going to have a giant bed and their names carved into the wall, like they’d been there for all eternity? Was it going to be somehow bloody and warm? Was it going to contain the names of all the bad deeds they had ever thought, the spelling of all the bad thoughts? Was it going to contain a small thought of evil and a magnifying glass?

They kept going. They walked past all the things Toby had so carefully considered and counted. Toby looked at the things she had been and gone through, counted all the things she had learned from them. 1, 2, 3… 15, 17. Now they could see the part of the world where they had gone the wrong way. In front was where their car might still be, but couldn’t be, already turned hard and glassy and stuck with the cold and frozen air here.

The beast, apart again or a third self, hovered and huffed near them in the dark and they listened to it, now holding hands, or each holding on to the hand of the other, pulling. It walked ahead, Susannah following, then Toby, waiting to see their home, and if it was their home.

They could tell which one theirs was. It was different; not a different color or different light, maybe a different shape, a crease in the rock that showed the comfortable spot Susannah would lean and Toby lean into her; maybe the air was thicker, to support their kind of being. They stopped outside, looking at it. The thick grey door, not smooth but rumpled; the soft bricks of different greys. Oh, they can see grey now. Probably because it’s their home. Probably it is really black, but they see it as grey, it looks so familiar to them; so familiar it’s even lightened, like the eye doesn’t have to fully saturate it, it knows what will be there. Or the eye saves the light it’s found and unspools it here, so it looks warmer.

They walk up to it together. It’s sort of round and small, with no chimney, but there are windows, two, and you can’t see in or out. They go to the front door. Susannah holds out her hand to knock, then holds back. She tries the door and it opens, quietly, with just that one creak that is needed for it to sound like home. She wonders where the demon is; but it’s fulfilled its mission and it’s gone now. Or something like that. She doesn’t ask if it’s inside them. Toby’s eyes aren’t burning anymore, they’ve maybe burned themselves out. Susannah looks inside. She doesn’t see any furniture just yet, no regular ways for them to live inside there. No refrigerators or bathtubs. Maybe there’s a staircase down into one of those small holes that are the bottom of the world; maybe that’s the real home, and the floor above is a decoy, or a large sign. Maybe they don’t need the regular ways to live here.

Susannah opens the door the rest of the way. She can smell something in there, not food but something similarly nourishing. Different air currents; air that goes through your ears and into your head and makes objects inside you, moves your brain, the little chemical molecules, so cute, turns them into something else. Whatever is in there, it smells like home. Or tastes. Or whatever the word is for when your brain absorbs something and changes shape as the blood configures into new beings. That kind of tasting.

Toby pokes her head in. There’s something here she doesn’t know if she likes. It’s strange standing next to Susannah now. Did they used to do this all the time? They didn’t used to walk one in front, one behind, one pulling back, one pulling forward? But next to each other? She thinks of herself and Susannah together in this very pure and bad place. Everything that had been inside her would be out, arrayed on the ground in front of them like laundry, hung in these very trees. She wants Susannah to squeeze her, hard, so hard her arms cut through Toby’s body and through to the inside and she hugs everything inside her, too. She doesn’t know if Susannah would be willing to do it. She could do it to her, though. Toby would not mind being covered in the black gunk of Susannah’s horrible insides, if there were any. She would love that. She rests her side against Susannah’s side. It’s been a very long night. It might have been more than one night. She remembers that they might be dead. She sighs and Susannah’s lungs take it up too.

Then Susannah says, “We’re out of eggs.”

“What?” Toby answers, probably not even out loud. Susannah shoves Toby out of the doorway, hard, at that same spot where their sides had just been touching. She grabs Toby, but not in a good way, she has both of her hands hard around Toby’s upper arm and pulls, she runs, she runs past the hut, past the other huts that are not theirs. She runs until she sees their car, a small and uninteresting bit of metal, a small inside-out freedom, and she pulls the passenger door open. It opens, maybe it’s not locked anymore or Susannah has understood the secret of locks or her hands have become the locks, and she shoves Toby inside, hard, and runs around to the other side as if not believing that Toby will stay put for any longer than a second.

She feels this pain deep inside her body, at the exact most inner place, small and sharp, like a knife stored there is beginning to cut her in two. A good, deserved, tight pain. She jumps into the car, turns the key, and zooms forward. She puts her foot all the way down and they climb, like Toby the spider had climbed, up a dark black road that is not in the place they live in, and then they are back on the roads, and she drives home fast. Very fast.

Toby slept for two days. Susannah tried to wake her sometimes for chicken broth but then let her be. She was sleeping the toxins out, sleeping the demon out. When she woke up they sat together at the small kitchen table and ate the eggs they had meant to have a few days ago. A quiet Monday, a sick day from work. They looked at each other’s eyes. Toby’s brown, tired; Susannah’s black, a little purple. “Are you okay?” Toby asked her.

June 5, 2024

About the writer

J. A. Hersh is a writer of speculative/odd fiction. She also works as a content designer/strategist and has a black belt from Modern Martial Arts in New York. Her writing has appeared in journals including Lady Churchill’s Rosebud Wristlet, Visitant, Five on the Fifth, Monkeybicycle, and Gone Lawn. She can be found at jahersh.com and on Bluesky at angelinammaist.bsky.social. She lives in Brooklyn with her girlfriend and their cats.

Further considerations

Lowcountry Blues and Judas Kiss

If I could feel sorrow // for a thing entire of itself, // it would be St. Helena Island.

The Next Note

Improvisations - little more than // preludes as inclined by other options // and expression as to what will happen